I recently attended a roundtable discussion on the Cost-Effectiveness of Peacebuilding hosted by the Alliance for Peacebuilding and the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) where IEP presented its report on Measuring Peacebuilding Cost-Effectiveness. As an Industrial Engineer and Certified Cost Analyst, I have spent my career analyzing costs in the software, consumer products, aerospace, technology, and defense industries. For those industries, cost is a critical factor in deciding how to allocate resources, establish budgets, measure performance and make trade-offs about investment decisions. I am excited that the peacebuilding community is beginning to examine the concepts of cost analysis and cost-effectiveness in order to make more informed decisions in allocating scarce resources. As I participated in the discussion and met with peacebuilders afterwards to share my experiences, I realized that the concepts of cost analysis and cost-effectiveness are new to many in this community. Understandably, there are many questions about their value, application to peacebuilding, and how findings would be used. Peacebuilders’ valid concerns about the application of cost analysis to their work fall into two primary categories related to findings and processes. Note: Cost analysis is a term used to describe the broader field of study that includes cost estimating / forecasting, should-cost analysis, and business case development. Cost-effectiveness studies are a subset of cost analysis which will be defined later in this blog entry. Findings: As the community works hard to empirically demonstrate the impact of peacebuilding programs and secure scarce resources, it can feel tangential at best, and threatening at worst, to focus on measuring the cost-effectiveness of peacebuilding programs. In our current political climate, some worry about diverting time and money away from what is perceived to be an existential battle for the future of peacebuilding to a more nascent evaluation agenda. Many are concerned that looking at cost might add fuel to the political fire by revealing opportunities to reduce spending on costly or ineffective programs. Throughout my career as a cost analyst, I have found the opposite to be true. Those organizations and programs that use the tools of cost analysis to strengthen the case for more resources typically end up with more funding, not less. For mission-driven and impact-hungry practitioners, cost analysis enables better decision making about where to spend each dollar across a program or portfolio to achieve greater impact. Processes: The second category of concern is related to processes. Many scholars and practitioners in the peacebuilding field ground their practice in systems-based approaches. Transforming interconnected social, political, and economic interests that drive violent conflict demands a complexity-aware approach. Systems thinking offers an invaluable mindset and toolkit. It is therefore promising that cost analysis has been tailored to complex, adaptive problems and corresponding programs. For example, it has been leveraged in similarly complex fields such as health care, space exploration, and advanced and emerging technologies (laser weapons, robotics, artificial intelligence). Complexity is not a reason to avoid cost analysis but it will require us to do so in systems-sensitive ways. For example, as we examine a portfolio of peacebuilding programs to determine their cost-effectiveness, we should include a spectrum of activities and programs that range from complicated (challenging technical programming such as community-oriented media programs to counter hate speech) to more complex (adaptive problems and programs such as support to transitional justice programs). A complex transitional justice program, such as support to prosecutors to convict a war criminal, might take millions of dollars over a couple of years, but could serve as a powerful deterrent to future warlords and conflict entrepreneurs, creating important ripple effects across a conflict eco-system. As is the case in other complex situations, cost is rarely the only factor in deciding between courses of action. Oftentimes the costlier option is the most prudent. The tools of cost analysis can demonstrate that while making the case for additional funding based on data and objective evidence. Regardless of the complexity of the environment, industry, program, or activity, there are three key questions that cost estimators seek to answer when performing cost analysis.

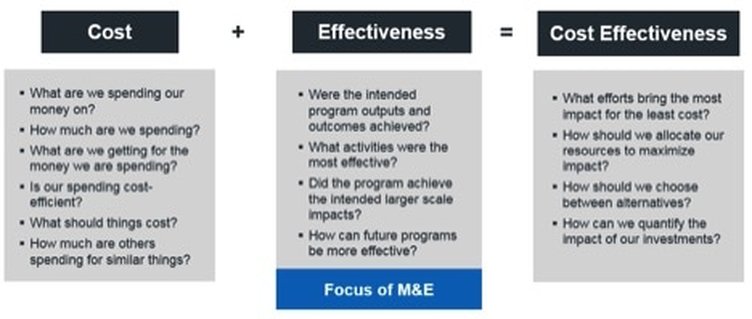

To determine a reasonable cost for an activity, cost estimators collect and analyze data to establish cost benchmarks and “should-cost” estimates. They also evaluate cost drivers that either increase or decrease the target cost of an activity and provide a method for establishing reasonable costs across different contexts and environmental conditions. This allows decision makers to evaluate the cost of alternatives and allocate resources to maximize effectiveness based on various funding levels. The ultimate goal of cost-effectiveness is to determine the optimal allocation of resources that provides the maximum effectiveness. Costly and ineffective activities should be eliminated in favor of low cost, highly effective activities. The figure to the right is a simple illustration of this principle. Those that are both effective and cost efficient (quadrant I) may warrant more funding and expanded implementation. Those that fall into quadrant IV (high cost and ineffective) should be eliminated so that resources are not wasted and can be re-allocated. Activities that fall into quadrant II and III warrant further investigation. For highly effective but costly activities, steps might be taken to reduce costs on those programs to make them more cost efficient. For low cost activities that are not achieving the desired outcomes, additional funding may increase their effectiveness making them better options than more costly alternatives. Increasingly, the peacebuilding community (practitioners, researchers, and donors) has committed resources to monitoring and evaluation (M&E) to measure both program outputs (did we do what we said we would do) and outcomes / effectiveness (did the program have the intended impact). M&E seeks to determine if a program was successful by determining the extent to which it achieved the desired outputs and outcomes. However, this view of success almost always ignores the question of whether the program objectives were achieved at a reasonable cost to the donor/funder. I believe most would agree that a successful peacebuilding / conflict prevention program should not only be effective but also cost-effective. The figure below highlights the key questions that cost analysts like myself traditionally seek to answer when evaluating cost-effectiveness. The UK’s Department for International Development has developed a similar concept to cost-effectiveness called Value for Money (VFM) that uses four principles to evaluate “the optimal use of resources to achieve intended outcomes”.

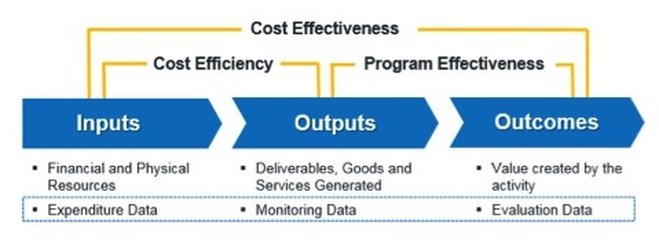

The VFM model presents a simple framework to apply the principles of cost-effectiveness to the peacebuilding community. Although the framework and concepts are simple, the task of collecting the necessary data can seem daunting. There are also many questions about whether the data even exists to evaluate cost-effectiveness for peacebuilding programs. After discussing this challenge with several experts in the peacebuilding community, I believe the data to answer the questions of cost efficiency, program effectiveness, and cost effectiveness are all available in the form of expenditure data (i.e. actual costs from accounting data) and M&E data as shown in the figure below. In my experience, one of the primary benefits of cost analysis is that it frequently identifies program’s that are insufficiently funded to achieve program objectives. Most of the programs that I have worked on as a cost estimator had insufficient funding because program budgets were based on overly optimistic and subjective assumptions instead of established cost benchmarks. I have also seen many programs awarded to the lowest bidder without any independent evaluation of whether the bid price was reasonable. These programs invariably fail to achieve the intended outcomes due to unrealistic and unreasonable budgets.

Establishing cost benchmarks for peacebuilding activities would provide insights into whether programs are sufficiently funded and increase the likelihood of program success for programs with insufficient funding. Cost analysis would allow funders to make informed decisions that balance the cost of activities with their expected benefits. In my time as a cost estimator, I have seen the use of cost analysis:

I believe that the peacebuilding community would experience many of these benefits by adopting the principles of cost analysis and developing a culture of cost awareness. At a time when U.S. government funding for peace and development programs is likely to decrease while violence is increasing, the need for cost analysis is more urgent than ever. Steve Sheamer is the Chief Operating Officer of Frontier Design Group, a consulting firm focused on solving the world’s most complex national and human security challenges. He has spent his entire professional career focused on reducing the cost of doing business through rigorous cost analysis, performance measurement, improved business processes, and technology implementation. He is a Certified Cost Estimator, Industrial Engineer, Lean Six-Sigma Black Belt, and Project Management Professional with over 15 years of experience supporting large, complex programs. His industry experience includes consumer product manufacturing, computer chip fabrication, aerospace and defense, and management consulting. He is passionate about identifying cost savings, improving program management processes, and implementing tools to improve the effectiveness of large, complex organizations and programs.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

October 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed